Chinese Ruler Who Cared for Art and Sex More Than Governing

| Mencius | |

|---|---|

| 孟子 | |

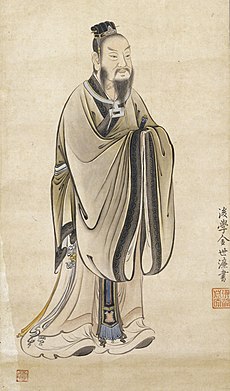

As depicted in the album Half Portraits of the Great Sage and Virtuous Men of Old ( 至聖先賢半身像 ), housed in the National Palace Museum | |

| Born | Mèng Kē 孟軻 372 BC Country of Zou, Zhou dynasty (present-day Zoucheng, Shandong) |

| Died | 289 BC (aged 82–83) State of Zou, Zhou dynasty |

| Resting place | Cemetery of Mencius, State of Zou, Zhou dynasty |

| Family |

|

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Chinese philosophy |

| School | Confucianism |

| Master interests | Ideals, social philosophy, political philosophy |

| Notable ideas |

|

| Influences

| |

| Influenced

| |

| Mencius | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Mencius" in seal script (top) and regular (lesser) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 孟子 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Mèngzǐ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Principal Meng" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bequeathed name: | Ji (Chinese: 姬; pinyin: Jī ) |

| Clan name: | Meng (孟; Mèng )[a] |

| Given proper noun: | Ke (simplified Chinese: 轲; traditional Chinese: 軻; pinyin: Kē ) |

| Courtesy name: | Unknown[b] |

| Posthumous name: | Chief Meng the Second Sage[c] (simplified Chinese: 亚圣孟子; traditional Chinese: 亞聖孟子; pinyin: Yàshèng Mèngzǐ ) |

| Styled: | Principal Meng (孟子; Mèngzǐ ) |

Mencius ( MEN-shee-əs);[one] born Mèng Kē (Chinese: 孟軻); or Mèngzǐ (Chinese: 孟子; 372–289 BC) was a Chinese Confucian philosopher who has oftentimes been described every bit the "second Sage", that is, after only Confucius himself. He is part of Confucius' fourth generation of disciples. Mencius inherited Confucius' ideology and developed information technology farther.[2] [3] Living during the Warring States period, he is said to have spent much of his life travelling effectually u.s. offering counsel to different rulers. Conversations with these rulers form the footing of the Mencius, which would later be canonised as a Confucian classic.

1 primary principle of his work is that human nature is righteous and humane. The responses of citizens to the policies of rulers embodies this principle, and a state with righteous and humane policies will flourish by nature. The citizens, with freedom from good dominion, volition and so classify fourth dimension to caring for their wives, brothers, elders, and children, and be educated with rites and naturally get better citizens.

Life [edit]

An image of Mencius in the sanctuary of the Mencius Temple, Zoucheng

Mencius, also known by his birth name Meng Ke ( 孟軻 ), was built-in in the Land of Zou. His birthplace is now inside the county-level city of Zoucheng, Shandong Province, simply thirty kilometres (eighteen miles) due south of Confucius's birthplace in Qufu.

He was an itinerant Chinese philosopher and sage, and one of the principal interpreters of Confucianism. Supposedly, he was a educatee of Confucius's grandson, Zisi. Similar Confucius, according to legend, he travelled throughout China for twoscore years to offer advice to rulers for reform.[4] During the Warring States menses (403–221 BC), Mencius served as an official and scholar at the Jixia University in the State of Qi (1046 BC to 221 BC) from 319 to 312 BC. He expressed his filial devotion when he took 3 years get out of absenteeism from his official duties for Qi to mourn his mother'southward expiry. Disappointed at his failure to consequence changes in his contemporary world, he retired from public life.[5]

Mencius was buried in the Cemetery of Mencius (孟子林, Mengzi Lin, too known equally 亞聖林, Yasheng Lin), which is located 12 km to the northeast of Zoucheng's central urban expanse. A stele carried by a giant rock tortoise and crowned with dragons stands in front of his grave.[6]

Mother [edit]

Mencius'south mother is often held up every bit an exemplary female effigy in Chinese culture. One of the nigh famous traditional Chinese iv-graphic symbol idioms is 孟母三遷 (pinyin: mèngmǔ-sānqiān ; lit. 'Mencius'southward mother moves 3 times'); this saying refers to the legend that Mencius'south mother moved houses three times earlier finding a location that she felt was suitable for the child's upbringing. As an expression, the idiom refers to the importance of finding the proper surroundings for raising children.

Mencius's begetter Meng Ji (孟激) died when Mencius was very immature. His mother Zhǎng ( 仉 ) or Meng Mu (孟母)[ clarification needed ] raised her son alone. They were very poor. At showtime they lived by a cemetery, where the mother found her son imitating the paid mourners in funeral processions. Therefore, the mother decided to motion. The next house was near a market in the town. There the boy began to imitate the cries of merchants (merchants were despised in early China). So the female parent moved to a house adjacent to a school. Inspired by the scholars and students, Mencius began to report. His mother decided to remain, and Mencius became a scholar.

Another story further illustrates the accent that Mencius's mother placed on her son's education. As the story goes, once when Mencius was immature, he was truant from school. His female parent responded to his apparent disregard for his teaching past taking upwardly a scissors and cutting the cloth she had been weaving in front of him. This was intended to illustrate that one cannot stop a task midway, and her instance inspired Mencius to diligence in his studies.

There is another legend about his mother and his wife, involving a time when his wife was at home solitary and was discovered past Mencius not to be sitting properly. Mencius thought his wife had violated a rite, and demanded a divorce. His mother claimed that it was written in The Book of Rites that before a person entered a room, he should announce his imminent presence loudly to permit others prepare for his arrival; equally he had non done that in this case, the person who had violated the rite was Mencius himself. Eventually Mencius admitted his fault.

She is 1 of 125 women of which biographies have been included in the Lienü zhuan ('Biographies of Exemplary Women'), written by Liu Xiang.

Lineage [edit]

Duke Huan of Lu's son through Qingfu ( 慶父 ) was the ancestor of Mencius. He was descended from Knuckles Yang of the Country of Lu ( 魯煬公 ). Duke Yang was the son of Bo Qin, who was the son of the Duke of Zhou of the Zhou dynasty royal family. The genealogy is constitute in the Mencius family tree ( 孟子世家大宗世系 ).[7] [8] [9]

Mencius's descendants lived in Zoucheng in the Mencius Family Mansion, where the Mencius Temple was likewise built and also a cemetery for Mencius'due south descendants.

Meng Haoran and Meng Jiao were descendants of Mencius who lived during the Tang dynasty.

During the Ming dynasty, i of Mencius's descendants was given a hereditary title at the Hanlin University by the Emperor. The title they held was Wujing Boshi (五經博士; 五經博士; Wǔjīng Bóshì).[10] [11] [12] In 1452 Wujing Boshi was bestowed upon the offspring of Mengzi-Meng Xiwen ( 孟希文 ) 56th generation[13] [fourteen] [15] [16] [17] and Yan Hui-Yan Xihui ( 顔希惠 ) 59th generation, the same was bestowed on the offspring of Zhou Dunyi-Zhou Mian ( 週冕 ) twelfth generation, the ii Cheng brothers (Cheng Hao and Cheng Yi-Chen Keren ( 程克仁 ) 17th generation), Zhu Xi-Zhu Ting ( 朱梴 ) 9th generation, in 1456–1457, in 1539 the aforementioned was awarded to Zeng Can'south offspring-Zeng Zhicui ( 曾質粹 ) 60th generation, in 1622 the offspring of Zhang Zai received the title and in 1630 the offspring of Shao Yong.[18]

One of Mencius's direct descendants was Dr. Meng Chih (Anglicised as Dr. Paul Chih Meng) old director of Communist china House, and managing director of the Communist china Institute in 1944. Time magazine reported Dr. Meng'south age that year as 44. Dr. Meng died in Arizona in 1990 at the age of 90.[19] North Carolina's Davidson College and Columbia University were his alma mater. He was attending a speech along with Confucius descendant H. H. Kung.[xx]

In the Republic of China at that place is an office called the "Sacrificial Official to Mencius" which is held by a descendant of Mencius, similar the post of "Sacrificial Official to Zengzi" for a descendant of Zengzi, "Sacrificial Official to Yan Hui" for a descendant of Yan Hui, and the post of "Sacrificial Official to Confucius, held by a descendant of Confucius.[21] [22] [23]

The descendants of Mencius still use generation poems for their names given to them by the Ming and Qing Emperors along with the descendants of the other 4 Sages (四氏): Confucius, Zengzi, and Yan Hui.[24] [25]

Historical sites related to his descendants include the Meng family mansion (孟府), Temple of Mencius (孟廟), and Cemetery of Mencius (孟林).

I of Mencius'due south descendants moved to Korea and founded the Sinchang Maeng clan.

Main concepts [edit]

Mencius, from Myths and Legends of People's republic of china, 1922 by E. T. C. Werner

Human nature [edit]

Mencius expounds on the concept that the human is naturally righteous and humane. It is the influence of gild that causes bad moral character. Mencius describes this in the context of educating rulers and citizens most the nature of man. "He who exerts his mind to the utmost knows his nature"[26] and "the mode of learning is none other than finding the lost mind."[27]

The four beginnings (or sprouts) [edit]

To show innate goodness, Mencius used the instance of a kid falling downwards a well. Witnesses of this event immediately feel

alarm and distress, not to proceeds friendship with the kid's parents, nor to seek the praise of their neighbors and friends, nor considering they dislike the reputation [of lack of humanity if they did not rescue the child]...

The feeling of commiseration definitely is the offset of humanity; the feeling of shame and dislike is the beginning of righteousness; the feeling of deference and compliance is the offset of propriety; and the feeling of right or wrong is the beginning of wisdom.

Men have these Iv Ancestry just as they have their 4 limbs. Having these Four Ancestry, but saying that they cannot develop them is to destroy themselves.[28]

Human nature has an innate tendency towards goodness, but moral rightness cannot be instructed downward to the last item. This is why only external controls e'er fail in improving gild. True improvement results from educational tillage in favorable environments. Also, bad environments tend to corrupt the homo will. This, however, is non proof of innate evil because a clear thinking person would avert causing damage to others. This position of Mencius puts him between Confucians such as Xunzi who thought people were innately bad, and Taoists who believed humans did not demand cultivation, they just needed to accept their innate, natural, and effortless goodness. The four beginnings/sprouts could abound and develop, or they could fail. In this way Mencius synthesized integral parts of Taoism into Confucianism. Individual effort was needed to cultivate oneself, just one's natural tendencies were proficient to begin with. The object of instruction is the cultivation of benevolence, otherwise known as Ren.[ citation needed ]

Instruction [edit]

According to Mencius, education must awaken the innate abilities of the human mind. He denounced memorization and advocated active interrogation of the text, saying, "One who believes all of a book would be better off without books" (盡信書,則不如無書, from 孟子.盡心下). 1 should bank check for internal consistency past comparison sections and debate the probability of factual accounts by comparison them with experience.[ citation needed ]

Destiny [edit]

Mencius also believed in the power of Destiny in shaping the roles of human beings in lodge. What is destined cannot be contrived by the human intellect or foreseen. Destiny is shown when a path arises that is both unforeseen and constructive. Destiny should non be confused with Fate. Mencius denied that Sky would protect a person regardless of his actions, saying, "One who understands Destiny will not stand up beneath a tottering wall". The proper path is i which is natural and unforced. This path must also be maintained because, "Unused pathways are covered with weeds." One who follows Destiny will live a long and successful life. One who rebels against Destiny will dice earlier his time.[ citation needed ]

Politics and economics [edit]

Mencius emphasized the significance of the common citizens in the state. While Confucianism by and large regards rulers highly, he argued that it is acceptable for the subjects to overthrow or fifty-fifty kill a ruler who ignores the people's needs and rules harshly. This is because a ruler who does not rule justly is no longer a true ruler. Speaking of the overthrow of the wicked King Zhou of Shang, Mencius said, "I have just heard of killing a villain Zhou, but I have not heard of murdering [him as] the ruler."[29]

This saying should not exist taken every bit an instigation to violence confronting regime but as an awarding of Confucian philosophy to social club. Confucianism requires a clarification of what may be reasonably expected in any given relationship. All relationships should be benign, but each has its own principle or inner logic. A Ruler must justify his position by interim benevolently earlier he can wait reciprocation from the people. In this view, a King is like a steward. Although Confucius admired Kings of great accomplishment, Mencius is clarifying the proper hierarchy of human society. Although a King has presumably college condition than a commoner, he is actually subordinate to the masses of people and the resource of society. Otherwise, there would be an implied condone of the potential of human society heading into the future. 1 is meaning simply for what 1 gives, not for what one takes.[ citation needed ]

Mencius distinguished between superior men who recognize and follow the virtues of righteousness and benevolence and inferior men who practise not. He suggested that superior men considered only righteousness, not benefits. That assumes "permanent property" to uphold mutual morality.[30] To secure benefits for the disadvantaged and the aged, he advocated free trade, low tax rates, and a more equal sharing of the revenue enhancement burden.[31]

In regards to the Confucian perspective of the market place, more than near Confucius' thoughts from Mencius than from the philosopher himself are learned. The government should accept a mostly hands-off approach regarding the market.[32] This was in part, to prevent state-run monopolies, withal, information technology was also the country's responsibility to protect against time to come monopolies that might come into beingness. Mencius besides advocated for no taxes on imports; the marketplace was to exchange for what you lacked so taxing merchants importing goods would ultimately injure the villagers. The thought behind this is that people are inherently good and rational and can exist trusted to regulate themselves, so price gouging or charade would not be an issue. Taxes on the holding were acceptable and to be the only means past which the dukes and states would collect money. They did not need to collect much considering taxes were only for supplemental funds.[32] These taxes were also progressive, pregnant the families that owned larger, more than fertile pieces of land would pay more than the families with uniform land allotments. Scarcity is an event in any market; notwithstanding, Mencius emphasizes the reframing of the idea of a scarce resource.[33] Instead of scarce, resource are to exist seen equally abundant. Resources are gained through work ethic not past whatever other means then there are no unfair competitions or gains. To preserve these natural resources, they needed to be used or harvested according to their cycles of growth or replenishing. In many cases, posterity has priority over profit.[34]

Influence [edit]

Mencius'due south estimation of Confucianism has generally been considered the orthodox version by subsequent Chinese philosophers, especially by the Neo-Confucians of the Vocal dynasty. Mencius's disciples included a large number of feudal lords, and he is said to take been more influential than Confucius had been.[35]

The Mencius (also spelled Mengzi or Meng-tzu), a volume of his conversations with kings of the time, is one of the 4 Books that Zhu Xi grouped every bit the core of orthodox Neo-Confucian thought. In contrast to the sayings of Confucius, which are short and self-contained, the Mencius consists of long dialogues, including arguments, with extensive prose. Information technology was generally neglected by the Jesuit missionaries who first translated the Confucian canon into Latin and other European languages, as they felt that the Neo-Confucian school largely consisted of Buddhist and Taoist contamination of Confucianism. Matteo Ricci as well particularly disliked what they had believed to be condemnation of celibacy equally unfilial, which is rather a mistranslation of a similar give-and-take referring more to aspects of personality. François Noël, who felt that Zhu'south ideas represented a natural and native development of Confucius'southward thought, was the start to publish a total edition of the Mencius at Prague in 1711;[36] [d] as the Chinese rites controversy had been recently decided against the Jesuits, all the same, his edition attained trivial influence outside central and eastern Europe.

In a 1978 book that estimated the hundred most influential persons in history to that point, Mencius was ranked at 92.[38]

Mencius Institute [edit]

The first Mencius Institute was established in Xuzhou, China in 2008 under a collaboration between Jiangsu Normal University, Cathay Zoucheng Heritage Tourism Bureau, and Xuzhou Mengshi Clan Friendship Network.[39]

Showtime Mencius Institute outside of Cathay is located at Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR) Kampar Campus, Malaysia in 2016.[39]

Encounter also [edit]

- Cheng Yi (philosopher)

- David Hume, whose ethical naturalism echoes Mencius's

- Lu Jiuyuan

- Sinchang Maeng association, Mencius is the founder of the Korean clan, Sinchang Maeng clan

- Wang Yangming

Notes [edit]

- ^ The original clan name was Mengsun (孟孫), afterward shortened into Meng (孟).[ citation needed ] It is unknown whether this occurred before or after Mencius's death.

- ^ Traditionally, his courtesy name was causeless to be Ziche ( 子車 ), sometimes incorrectly written as Ziyu ( 子輿 ) or Ziju ( 子居 ), simply recent scholarly works show that these courtesy names appeared in the 3rd century AD and use to another historical figure named Meng Ke who also lived in Chinese antiquity and was mistaken for Mencius.[ commendation needed ]

- ^ , meaning 2d simply to Confucius. The name was given in 1530 by the Jiajing Emperor. In the two centuries before 1530, the posthumous proper name was "The Second Sage Duke of Zou" ( 鄒國亞聖公 ) which is still the proper name that can be seen carved in the Mencius ancestral temple in Zoucheng.[ commendation needed ]

- ^ Noël's transcription of the proper noun as "Memcius or Mem Tsu" reflects the orthography of his mean solar day, which rendered /ŋ/ as ⟨grand⟩. Run across, e.g., "Nankim" for "Nanjing" and "Kiamnim" for "Jiangning" on the map of China published in the 1687 Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese.[37]

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ "Mencius". Random House Webster's Entire Lexicon.

- ^ Mei, Yi Pao (1985). "Mencius", The New Encyclopedia Britannica, five. eight, p. 3.

- ^ Shun, Kwong Loi. "Mencius". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy . Retrieved 18 Nov 2017.

- ^ Chan 1963: 49.

- ^ Jaroslav Průšek and Zbigniew Słupski, eds., Dictionary of Oriental Literatures: Eastward Asia (Charles Tuttle, 1978): 115-116.

- ^ 孟子林 Archived 2012-08-05 at archive.today (Mencius Cemetery)

- ^ 《三遷志》,(清)孟衍泰續修

- ^ 《孟子世家譜》,(清)孟廣均主編,1824年

- ^ 《孟子與孟氏家族》,孟祥居編,2005年

- ^ H.S. Brunnert; V.V. Hagelstrom (15 April 2013). Present Day Political Organization of China. Routledge. pp. 494–. ISBN978-one-135-79795-9.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-25. Retrieved 2016-04-17 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Present 24-hour interval political organisation of China". archive.org.

- ^ "熾天使書城----明史". angelibrary.com.

- ^ "Kanripo 漢籍リポジトリ : KR2m0014 欽定續文獻通考-清-嵇璜". kanripo.org.

- ^ Sturgeon, Donald. "欽定歷代職官表 : 卷六十六 - 中國哲學書電子化計劃". ctext.org.

- ^ "明史 中_翰林院". inspier.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-05-09 .

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-10-04 .

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived re-create as title (link) - ^ Wilson, Thomas A.. 1996. "The Ritual Formation of Confucian Orthodoxy and the Descendants of the Sage". The Journal of Asian Studies 55 (iii). [Cambridge University Press, Association for Asian Studies]: 559–84. doi:x.2307/2646446. JSTOR 2646446 p. 571.

- ^ "Paul Chih Meng, 90, Headed China Establish". The New York Times. 7 February 1990.

- ^ "Educational activity: Prc Firm". TIME. Sep 4, 1944. Archived from the original on December 14, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ^ "台湾拟将孔子奉祀官改为荣誉职 可由女性继承_台湾频道_新华网". xinhuanet.com.

- ^ "台湾儒家奉祀官将改为无给职 不排除由女子继任_新闻中心_新浪网". sina.com.cn.

- ^ 台湾拟减少儒家世袭奉祀官职位并取消俸禄 [Taiwan intends to reduce Confucian hereditary positions and cancel the bacon.]. rfi.fr (in Chinese).

- ^ (in Chinese) 孔姓 (The Kong family, descendents of Confucius) Archived 2011-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Chinese) 孟姓 (The Meng family, descendents of Mencius) Archived 2006-01-16 at the Wayback Motorcar

- ^ The Mencius 7:A1 in Chan 1963: 78.

- ^ The Mencius 6:A11 in Chan 1963: 58.

- ^ The Mencius 2A:6 in Chan 1963: 65. Formatting has been applied to ease readability.

- ^ The Mencius 1B:8 in Chan 1963: 62.

- ^ Yagi, Kiichiro (2008). "China, economic science in," The New Palgrave Lexicon of Economics, v. 1, p. 778. Abstract.

- ^ Hart, Michael H. (1978), The 100: A Ranking of the Well-nigh Influential Persons in History, p. 480.

- ^ a b (1881-1931)., Chen, Huanzhang (1911). The economic principles of Confucius and his school. Columbia University, Longmans, Green & Co., Agents; [etc., etc.] OCLC 492146426.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Manor, The Arthur Waley (2012-11-12). The Analects of Confucius. doi:10.4324/9780203715246. ISBN9780203715246.

- ^ Martin, Michael R. (1990-02-01). "David L. Hall and Roger T. Ames, Thinking Through Confucius, State University of New York Printing, 19137". Periodical of Chinese Philosophy. 17 (four): 495–503. doi:ten.1163/15406253-01704005. ISSN 0301-8121.

- ^ Charles O. Hucker, Prc to 1850: A Short History, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1978, p. 45

- ^ Noël (1711).

- ^ "Paradigma 15 Provinciarum et CLV Urbium Capitalium Sinensis Imperij [A Schematic of the fifteen Provinces and 155 Chief Cities of the Chinese Empire]", Confucius Sinarum Philosophus... [Confucius, Philosopher of the Chinese...] , Paris: Daniel Horthemels, 1687, Bk. III, p. 104 . (in Latin)

- ^ Hart, Michael H. (1978), The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History, p. 7, discussed on pp. 479–81.

- ^ a b "Proud addition to university". The Star.

Bibliography [edit]

- Chan, Alan K. Fifty. (ed.), 2002, Mencius: Contexts and Interpretations, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Chan, Wing-tsit (trans.), 1963, A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Academy Printing.

- Graham, A.C., 1993, Disputers of the Tao: Philosophical Argument in Aboriginal China, Chicago: Open Court Printing. ISBN 0-8126-9087-vii

- Ivanhoe, Philip J., 2002, Ideals in the Confucian Tradition: The Idea of Mencius and Wang Yangming, 2nd edition, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- Liščák, Vladimir (2015), "François Noël and His Latin Translations of Confucian Classical Books Published in Prague in 1711", Anthropologia Integra, vol. vi, pp. 45–52 .

- Liu Xiusheng; et al., eds. (2002), Essays on the Moral Philosophy of Mengzi, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing .

- Noël, François, ed. (1711), "Sinensis Imperii Liber Quartus Classicus Dictus Memcius, Sinicè Mem Tsu [The Fourth Classic Book of the Chinese Empire, Called the Mencius or, in Chinese, Mengzi]", Sinensis Imperii Libri Classici Sex [The Six Archetype Books of the Chinese Empire] , Prague: Charles-Ferdinand University Press, pp. 199–472 . (in Latin)

- Nivison, David South., 1996, The Ways of Confucianism: Investigations in Chinese Philosophy, La Salle, Illinois: Open Court. (Includes a number of seminal essays on Mencius, including "Motivation and Moral Action in Mencius," "Two Roots or One?" and "On Translating Mencius.")

- Shun, Kwong-loi, 1997, Mencius and Early Chinese Thought, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Van Norden, Bryan Westward. (trans.), 2008, Mengzi: With Selections from Traditional Commentaries, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing.

- Van Norden, Bryan W., 2007, Virtue Ethics and Consequentialism in Early Chinese Philosophy, New York: Cambridge Academy Press. (Chapter 4 is on Mencius.)

- Wang, Robin R. (ed.), 2003, Images of Women in Chinese Thought and Culture: Writings from the Pre–Qin Menstruum through the Vocal Dynasty, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. (Encounter the translation of the stories about Mencius'southward mother on pp. 150–155.)

- Yearley, Lee H., 1990, Mencius and Aquinas: Theories of Virtue and Conceptions of Courage Albany: State Academy of New York Press.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Eatables has media related to Mencius. |

| | Wikiquote has quotations related to Mencius . |

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Mengzi: Chinese text with English translation and links to Zhuxi's commentary

- English translation by A. Charles Muller Annotated scholarly translation with Chinese text

- Article discussing the view of ethics of Mencius from The Philosopher

- Works past Mencius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or well-nigh Mencius at Internet Archive

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mencius

0 Response to "Chinese Ruler Who Cared for Art and Sex More Than Governing"

Post a Comment